Military & Veterans Life

Cover Story: Tuskegee Airmen

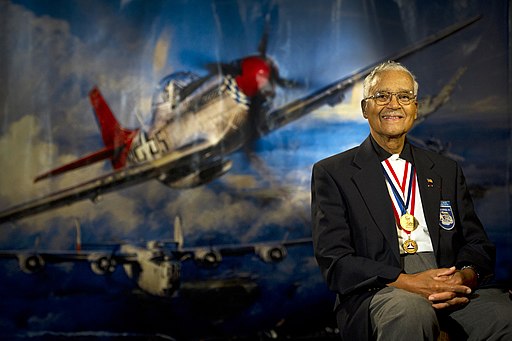

“Don’t let negative circumstances be an excuse for not achieving,” said Air Force Colonel Charles McGee, a Tuskegee Airman who passed away last month. The Tuskegee Airmen are a legendary group of Black soldiers and pilots in World War II who helped racial equality take off in the military. McGee was one of the oldest remaining Airmen before he died recently at the age of 102.

In a time when racism and segregation reigned, McGee and his fellow Black military personnel worked hard to prove themselves.

“Although the Army didn’t believe in our capabilities, they didn’t change the training standards, and that was a plus for us, that we were able to meet the standards and perform successfully,” the Ohio native had said of his training.

The Tuskegee Airmen were the first Black military pilots in the United States in the 1940s. There were 992 pilots trained at Tuskegee Institute in Alabama. With ground personnel, aircraft mechanics, and logistical personnel, there were over 14,000 total Tuskegee Airmen, but not many remain alive today. The Tuskegee Airmen achieved a remarkable war record; they shot down a total of 112 enemy aircraft in the air and 150 on the ground, 600 rail cars, 350 trucks and other vehicles, and 40 boats and barges during World War II.

an interview with Robert Wynn of Lucasfilm at the Tuskegee Airmen's

40th national convention at the Gaylord National Hotel in National

Harbor, Md., Aug. 4, 2011.

In his 30 years of active service, Colonel McGee completed 409 air combat missions across three wars: World War II, Korea, and Vietnam. He served as a founder and president of the Tuskegee Airmen Association. He is survived by three children, 10 grandchildren, 14 great grandchildren, and one great-great grandchild.

“The Tuskegee Airmen proved beyond a shadow of a doubt that African-Americans were capable of flying the best of the Allied fighters to victory against the best of the enemy fighters,” wrote Dr. Daniel L. Haulman of the Air Force Historical Research Agency. “They earned an indelible place in the history not only of their service, but also in the history of their country and of the world”.

President Franklin Roosevelt was the first leader to take the steps towards changing the racial status in the military during the difficult period of segregation. While running for his third term in office, he promised to give black pilots the chance to train to serve in the Army Air Corps (before it became the Air Force).

A year later, the War Department invested in building a base for that training in Tuskegee, Alabama, where the Tuskegee Institute had already been training black civilian pilots. Following their training, pilots were assigned to the 99th Fighter Squadron, and later to the 100th, 301st, and 302d Fighter Squadrons of the 332d Fighter Group.

The 99th Fighter Squadron flew 577 missions before joining the 332nd Fighter Group, and the 332nd Fighter Group flew 914 missions, for a total of 1491 combat missions flown by the Tuskegee Airmen. It was thought during the war that in over 200 escort missions, the Tuskegee Airmen had never lost a bomber. Years later, a detailed analysis found that enemy aircraft shot down 27 bombers they escorted, a much better success rate than other escort groups of the 15th Air Force, which lost an average of 46 bombers.

After battle, the Airmen returned home to a country still rife with racial inequality. But their work eventually led President Harry Truman to issue Executive Order 9981 in 1948, which desegregated the U.S. Armed Forces and mandated equality of opportunity and treatment. While the military took time to put this into action, the Air Force was the first to achieve significant racial segregation in 1949.

The Tuskegee Airmen were awarded the Congressional Gold Medal by President George W. Bush in 2007 (pictured, top of the article) and their story was the basis for George Lucas’ 2017 film “Red Tails” and the play “Fly,” which opens this weekend in New Orleans. Their most recent honor came in January 2022: the Tuskegee Airmen received the Top Gun recognition 73 years after winning the first gunnery competition among pilots from across the Air Force.