Military & Veterans Life

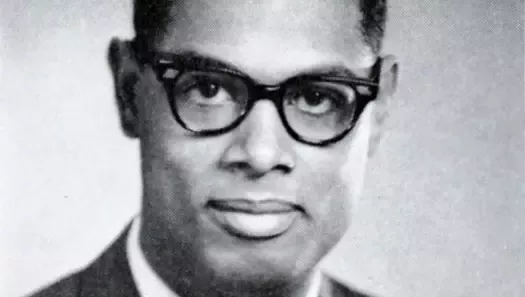

Member Stories: After 40 Years, Ed Dyke Opens Up About Surviving 2 Deadly Assaults During WWII

Bernard Edelman

Ed Dyke never talked about his war. Like most veterans who have been seared body and soul by the sudden and sustained assaults of combat, he kept his memories locked away from the family he loves. Yet these memories were never very far from his consciousness.

Every night, he says, he thinks about his experiences aboard the USS Buck, and then the USS Meredith, plying the waters of the North Atlantic. In his mind’s eye, he still sees the explosions that sank both ships on which he served. He sees the bodies floating on oil slicks. He hears the cries of the dying. He sees himself in the hospital in England, recovering from the severe burns he suffered when the Meredith went down.

This all changed in 1985, 40 years after Ed Dyke came home from the war. His nine children were grown by then. He was a grandfather. Veterans of another war, the sons and daughters of those who served in what Studs Terkel dubbed "the Good War," dedicated a memorial and held a parade in New York City.

And Ed Dyke opened up.

A Flood of Memories

On May 8, the day after the "Welcome Home" parade down New York’s "Canyon of Heroes," Ed and son-in-law Pat Mulhearn were standing in front of Pat’s house in Riverdale, New York, when Ed, who now lives in Lexington, Massachusetts, began to talk about the guys with whom he had served. It was as if the spigot that everyone had thought was frozen shut had opened, releasing a torrent of memories.

"He said he was going to reach out to the guys he’d served with," says Pat, who then had been counsel to New York City Mayor Ed Koch and is now a principal of the Milestone Management Group in White Plains, New York. "He said he wanted to get together with them."

And get together they did.

"His whole group had been the same way," says Edna, his wife of 51 years. "They did not talk about the war to their families." They did open up at the reunions that followed, tearful yet joyous affairs of reflection and reminiscence. There were, however, never that many survivors to start with, says Ed, and many of those who are still alive are not in the best of shape, so there likely will be few, if any, more reunions.

Two Hits

"I went to war for my country and I would do it all over again," Ed says in a telephone conversation, his Yankee roots immediately apparent. He cautions that he might get emotional. "I left a lot of good friends behind," he says.

Ed enlisted in the Navy on December 8, 1941, the day after the sneak attack on Pearl Harbor. Trained as a machinist’s mate, he was assigned to the USS Buck, a destroyer. At around 10:00 p.m. on August 22, 1942, while on convoy duty, the Buck was rammed by the troop transport SS Awatea out of Halifax, Nova Scotia. "Maybe 20, 30 feet of fantail was sheared off" his ship, he says. Twelve men were killed.

That wasn’t the worst of the night, his first brush with death.

The USS Ingraham, which had been racing through the fog to our rescue, collided with another ship, Ed says. "Within seconds, there was this enormous explosion. It was awful. Of a crew of 300, one officer and eight men survived."

A year later, the Buck, which had undergone repairs in Boston, participated in the invasion of Sicily on July 10. On August 2, accompanying a convoy in the Mediterranean, the crew used depth charges to sink the Italian submarine Argento. They picked up 46 survivors. Two months later, just after midnight on October 8-9, Ed was down in the engine room when the Buck made contact with the German sub, the U-616, off Salerno Gulf. This time, however, the bad guys won the engagement.

"We found out later that they fired a new torpedo that had never even been tested," Ed says. "It hit us right in the forward magazine." Those who survived the initial explosion were forced to abandon ship. Ed had to climb up from the engine room to get free of the sinking ship. He was able to swim to a raft. As he was hoisting himself up, another explosion "just blew the life jacket off my back," he says. Although shaken, wet, and cold, he had survived, one of 69 men and seven officers to make it through the hellish night. Some 150 others did not.

Until he was picked up 23 hours later, Ed and his mates floated through an oil slick, the stench of burning oil and the cries of the dying permeating the air. It was not an easy experience to bury.

D-Day Plus Two

Ed was subsequently assigned to the Meredith, a "brand new" destroyer. On June 8, 1944, two days after providing pre-invasion shore bombardment for the D-Day landing on Utah Beach, the Meredith was sunk in the Bay of the Seine. A mine exploded, opening a 65-foot hole in its port side. The ship flooded fast. Two officers and 33 crewmembers perished. Ed, who was the last man in the engine room to make it out, suffered first- and second-degree burns over almost 50 percent of his body - and the loss of all ten of his fingernails.

Somehow, in the chaos, in the darkness, "I made it up and over the side," he says. He was picked up within a half-hour by another destroyer. And within a day, he was in the 158th General Hospital in England, where he would remain for the next two months.

"Those first days in the hospital, the pain was so bad I prayed that I’d die," Ed says. After three or four days, though, "I thanked God for not taking me."

His war was over.

Putting It Behind Him

Ed was honorably discharged in January 1945. He returned to his home in Somerville, Massachusetts. He used his GI Bill benefits to study refrigeration and air-conditioning maintenance and repair. He married his Edna on July 11, 1950. And until 1985, he was close-lipped about the war that was with him every day.

As Ed started reaching out to his former shipmates, he learned that several of them thought he had perished when the Meredith went down. "We called you more times than your mother called you for dinner," one of his buddies wrote back to him. "We thought you were dead."

At one reunion, in Norfolk, Virginia, while drinking beer with his buddies on the fantail of a cruise ship, "a guy came over. He had seen ’USS Buck 420’ on my cap. He said, ’I know the captain that sank that ship.’ Seems that he had spent 20 years on submarine duty," and by then West Germany was a member in good standing of the Free World, a partner in NATO, an ally against the Soviet Union.

One of his buddies, George Brooks, wrote to the German captain, Siegfried Koitschka. In his reply, the captain said he "remembered that night so clearly. You were coming at us so fast, it had to be either you or us."

The reunions were bittersweet. "Only seven of us from the Buck showed up at the last one," Ed says. There had been 70 survivors, "only ten or so are left now."

Ed speaks with some of them, with George Brooks and with Ed Cummings and with Carl Dufresne, every three or four months. Carl and Cliff Smedstead showed up to help him celebrate his 80th birthday last year.

But his family, his children and his grandchildren, now understand more about their patriarch. And they now know why, when he’d accompany them to the beach when they were young, he would never go into the water.