WeSalute Awards

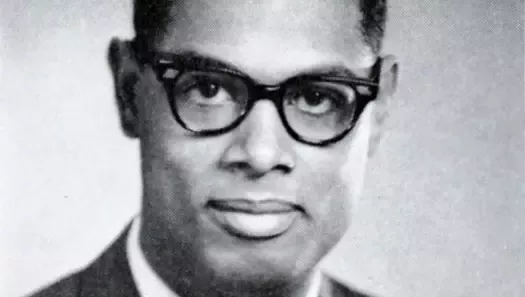

TopVet: Dr. Phillip Shinnick

A world record holder, Olympic athlete, and Air Force Captain, Dr. Phillip Shinnick has an extensive track record of achievements But at 79 years old, perhaps his most admirable accomplishment is his tenacity.

A world record holder, Olympic athlete, and Air Force Captain, Dr. Phillip Shinnick has an extensive track record of achievements But at 79 years old, perhaps his most admirable accomplishment is his tenacity.

It took Shinnick 58 years to earn credit for his world record long jump.

“I did something that was fantastic and it came back to me as something terrible,” he said in an exclusive interview with Veterans Advantage.

Shinnick attended the University of Washington on a track and field scholarship. During his first season, he was invited to the California Relays in Modesto.

“It was the best track meet in the history of the United States – better than the Olympics. Every athlete from around the world was there,” Shinnick said.

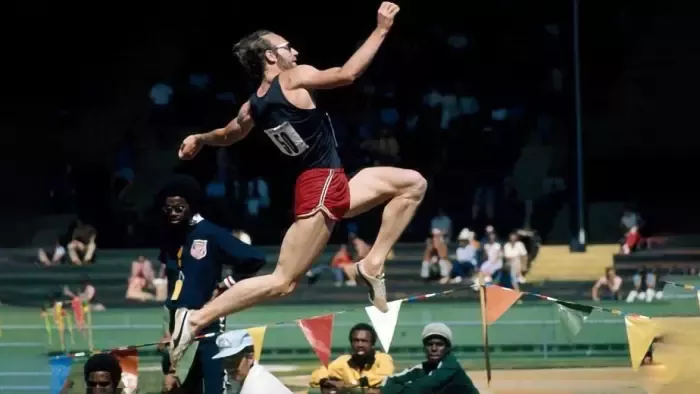

After grabbing a burger and a milkshake, he went to the field. Shinick was placed in the last heat of the long jump, just before Ralph Boston, an Olympic Champion and world record holder who was expected to break the world record again that day.

On Shinnick’s second jump, his right foot landed at 27 feet 10 inches and his left foot was 27 feet 5 inches.

“I was off balance. It didn’t go that well but nevertheless, it was past the world record, which was 27-3 ¾.” They remeasured again and again, just to make sure. The sand caved in after these tries, making it 27’4”, a new long jump World Record. Shinnick was named the Outstanding Athlete of the Meet.

But later, back at his Sigma Nu fraternity, Shinnick found out publicly that the jump wasn’t counted. A recent new rule required an altimeter to measure the wind for every long jump. There was no recording for Shinnick’s jump, as the altimeter was being used at another event. At the other event, which was right beside the long jump, the altimeter had not recorded any wind—but still, there was no record for Shinnick’s jump.

The next morning, top officials at the meet voted to verify Shinnick’s record. There hadn’t been time to purchase another altimeter; the rule couldn’t—or shouldn’t--be enforced. Dr. Shinnick thought he had the World Record.

The record, however, was never submitted by the U.S for international approval. Sports administrators were keeping the record quiet for political reasons, Shinnick later surmised.

The Spokane, Washington native, who hung model airplanes from his ceiling as a kid, Shinnick spent 10 years in the Air Force. At 6’3”, he was too tall to fly, yet he joined the Air Force ROTC at University of Washington and then worked as a Captain in Air Force Systems Command. “The military was really good to me,” he reflected. “I’m a big advocate for the military as a place to be when you’re at a young age to learn teamwork, do your duty, and have meaningful work.”

The Spokane, Washington native, who hung model airplanes from his ceiling as a kid, Shinnick spent 10 years in the Air Force. At 6’3”, he was too tall to fly, yet he joined the Air Force ROTC at University of Washington and then worked as a Captain in Air Force Systems Command. “The military was really good to me,” he reflected. “I’m a big advocate for the military as a place to be when you’re at a young age to learn teamwork, do your duty, and have meaningful work.”

He attended Officers Training School 18 days before the 1964 Olympic trials and remembers the challenges of being part of both worlds. “It was very difficult. I wanted to make the Olympic team. I ran in my combat boots in the mountains before the sun came up.”

He did make the Olympic team and represented the United States in the 1964 Olympics in Tokyo. He was then Commissioned as an Air Force Officer in 1965.

After more than a decade of competing, Dr. Shinnick went on to earn a PhD from the University of California, Berkeley, and became a professor at Rutgers University. In 1984, he became a professor at New York Medical College as well as an editor of medical journals. He spent 20 years as an associate doctor in clinics in New York and obtained a national license in Traditional Chinese Medicine.

After more than a decade of competing, Dr. Shinnick went on to earn a PhD from the University of California, Berkeley, and became a professor at Rutgers University. In 1984, he became a professor at New York Medical College as well as an editor of medical journals. He spent 20 years as an associate doctor in clinics in New York and obtained a national license in Traditional Chinese Medicine.

Through all his other accomplishments, however, Shinnick never gave up on the recognition for his long jump: he wrote countless letters and articles lobbying for his record. He waited for certain leaders to retire.

“I realized I was the only one who could bring justice to myself,” Shinnick said. “I met at every level of sport for 58 years with sports officials.

Finally, in 2003, Shinnick’s long jump became the American record. It took until 2021 to finally be recognized as the world record by the Court of Arbitration of Sport.

The road was long. “When the world is against you like it was for me and my record, it can make you lonely.” Shinnick credits self care as a key to his success. “If I could take care of myself physically and emotionally, then I would not be harmed and would win.”

Shinnick knows both the importance and the challenges of this type of self-work, particularly when one has a history of trauma. His older brother, Nelson Shinnick, USMC, served as a Huey armored helicopter pilot in Vietnam and flew daily combat missions. He was one of only three pilots in his squadron to return home alive. The other two committed suicide. Captain Nelson Shinnick began having nightmares around age 40. Unable to handle his trauma and suffering from war, he slipped into alcohol and retreated from life. He survived until age 70 only by maintaining contact with the Marines he saved by diverting fire to himself. (“Besides me, they were his other brothers,” said Shinnick.)

Shinnick knows both the importance and the challenges of this type of self-work, particularly when one has a history of trauma. His older brother, Nelson Shinnick, USMC, served as a Huey armored helicopter pilot in Vietnam and flew daily combat missions. He was one of only three pilots in his squadron to return home alive. The other two committed suicide. Captain Nelson Shinnick began having nightmares around age 40. Unable to handle his trauma and suffering from war, he slipped into alcohol and retreated from life. He survived until age 70 only by maintaining contact with the Marines he saved by diverting fire to himself. (“Besides me, they were his other brothers,” said Shinnick.)

Shinnick has been very motivated to help those struggling with similar traumas. Though he doesn’t see as many patients these days, he has worked with people of all walks of life, including veterans. He publishes self-help methods and encourages people to heal themselves, as he did.

“You have to take care of yourself.,” he advises. “You have to work on it on a daily basis. It’s a full-time job when you’re under trauma.” He equates it with his pursuit of his world record that took nearly a lifetime. “Never let it go. Work on it, work on it, work on it.”