WeSalute Awards

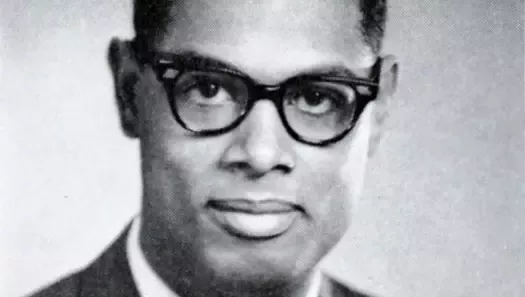

HeroVet Duery Felton, Jr., Curator of the Vietnam Veterans Memorial Collection

Vietnam Veterans Memorial Collection curator Duery Felton Jr. often stands amid boxes that store items left at the Wall. Felton and his staff also oversee collections from over 40 other regional National Park Service sites, such as the Clara Barton House, Ford's Theatre and the Lee Mansion. Thirty-five years ago, he was one of McNamara’s 100,000, part of the big draft call of November 1966. He went from high school to Vietnam with minimal training in between – basic at Ft. Gordon; advanced infantry at Ft. Jackson – to meet the critical need for bodies as the American presence in the war rapidly escalated.

Today, Duery Felton, Jr., who barely survived his time in country, is a very special veteran: Duery Felton is Curator of the Vietnam Veterans Memorial Collection, the repository of the "artifacts" left by visitors to the national Vietnam Veterans Memorial in Washington, D.C.

For Duery, this position with the National Park Service, which he has held for a decade, is more than a job. It is a calling, a sacred trust. "I am honored," he says simply of his role.

Duery Felton was profoundly changed by his time in the service. Just as he was scarred on the outside by grievous wounds suffered during a search-and-destroy operation while he was assigned to the Army’s 1st Infantry Division as a platoon radio operator, so is he steeled on the inside by the injustice of what befell too many young men – young and poor, black men and white and Hispanic -- drafted during the early years of the war. Young men like Duery Felton.

He had spent ten-and-a-half months in Vietnam, operating near the Cambodian border "and probably in Cambodia as well" when he was hit. One of the last things he recalls before losing consciousness is someone telling him that if he wakes up he would have to cover his throat because of the tracheotomy he underwent that saved his life. Beyond revealing this single fact, he is reluctant to talk much about the firefight on a bridge in which his life almost ended. He does acknowledge that he has spent some 30 years in and out of hospitals undergoing rehabilitative surgeries; he does intimate that every day since Vietnam he has been in pain.

For years after he was discharged from the Army, the Washington, D.C. native held a variety of jobs, at the World Bank, at the Department of Housing and Urban Development. Then he found himself in the right place at the right time. A member of Vietnam Veterans of America, he read in the VVA Veteran about the situation resulting from the unanticipated avalanche of artifacts left by visitors to the Vietnam Veterans Memorial. In 1984, two years after the groundbreaking of the memorial, the National Park Service/National Capital Region was given stewardship of the the memorial. At this time, Regional Curator Pam West determined that these mementos would become a museum collection under the care of the National Park Service and everything, except for unaltered American flags and living plant matter, would be saved and catalogued.

This is where Duery fits in.

One day, visiting the collection, he noticed that several objects had been mislabeled. The curatorial staff, it seems, had no frame of reference to understand some of the items that had been left, like some souvenir pieces from Thailand brought back by a GI from R&R. He pointed this out. Shortly thereafter, he was hired. And his job, his calling, has seen him evolve into a highly respected member of the veterans’ community, a man who brings passion and resolve and commitment to his "government job."

A ‘Sacred Trust’

Upwards of 65,000 artifacts currently comprise the collection. They are featured in books, on documentaries, on news shows like "Nightline," which gave the collection its initial national exposure back in 1986.

In the collection are letters and postcards and poems penned by buddies and lovers, parents and siblings and children.

"Occasion cards": "This would have been Wiley’s 50th birthday;" Photographs. Pictures of children inscribed, "This should have been our child." Books. Old LPs and eight-tracks. A CD entitled, "Here’s that Sunshine Day." C-ration cans. Diplomas (left by the children of KIAs).

Many express the raw emotions of loss of a loved one, a good friend, a comrade in arms; of lives cut short by a bullet or a bomb in a war so many are still grappling to come to terms with. Some messages are written of the moment by visitors overcome with emotion.

Others have been carefully prepared back in Lima, Ohio, or Metter, Georgia, or Skillman, New Jersey, brought to the memorial during a visit, and left almost as an offering.

Are there any particular artifacts that have special meaning to Duery Felton?

There is a black beret with the 101st Airborne Recon insignia, he says, left by a surviving member of a recon team. "Why did he wait 20 years to leave it?" Duery wonders. "What was he going through all those years? Was he suffering from survivor’s guilt? Did leaving the beret help him heal in any way?"

Duery was processing artifacts one day when he came across a manila envelope. "Duery, you will understand" was all it said on the outside. Inside was the combat diary of a veteran.

Then there was a neckerchief in a Ziploc bag, with a photo of a black Marine and a white Marine. The black Marine left the photo to honor the memory of his buddy, who had been killed in action. "When I opened the bag, it had that smell of Vietnam," says Duery, whose own memories are as painful as the wounds that continue to plague him.

Fifteen hundred mementos left at the memorial during the first nine years, are part of an ongoing exhibit at the Smithsonian. Opened in 1992 to commemorate the tenth anniversary of the memorial, it was slated to run six months. But the overwhelming response has given the exhibit, one of the most popular at the museum, an open-ended stay.

Duery, along with fellow members of his VVA chapter, has spent Thanksgiving day and Christmas morning in recent years delivering packages of goodies to hospitalized veterans. "These guys still are in the hospital dealing with that experience," he says. "For them, the war never really goes away."

Nor does it for Duery Felton.

Image Credit: http://www.npr.org/2016/11/12/501623765/watcher-at-the-wall-one-veteran-finds-a-lifeline-in-all-thats-left-behind