WeSalute Awards

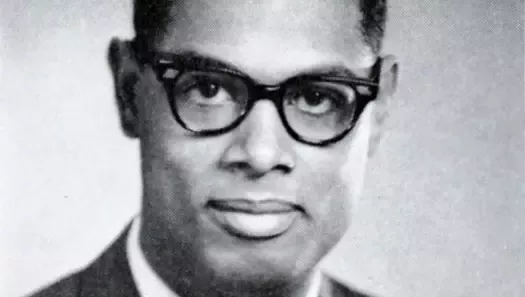

HeroVet: Tyrone T. Dancy, Serving His Fellow Veterans with Passion and Commitment

Bernard Edelman

“I feel there’s an obligation here,” says Tyrone T. Dancy, veterans’ employment program supervisor with the Pennsylvania Department of Labor. For almost a quarter of a century, he has been helping fellow veterans get the assistance they need – assistance they’ve earned – to steer them to productive lives. His motto could be “Service with a smile”; his goal is to “really help those who seek and need help.” And his satisfaction comes from those he’s assisted. “Because when you’re helpful and treat them with respect,” he says, “they really appreciate it.”

Tyrone brings commitment and passion to his job. Because for him it’s more than a job: Tyrone Dancy is another veteran whose life began after he almost lost it, in a firefight in Vietnam. He understands the sacrifice of service.

Born and raised in Philadelphia, he hails from a family that “knows firsthand the pledge of allegiance to America,” as he’s written. His grandfather, John Strayhorn, was wounded while serving in World War I. His uncle, James Strayhorn, served in the Korean War and nearly lost his legs. His father, Leon Dancy, also suffered injury during the Korean War.

Then it was Tyrone’s turn.

Short Operation

Drafted in January 1969, he found himself in Vietnam by June. Assigned to the 199th Light Infantry Brigade operating out of Long Binh, his first search-and-destroy mission was his last.

The third day of the operation, he wrote in his book, War Aftermath Depose, was “another long, torturous hot, humid day of deadly hide and seek. I was constantly looking where I was placing my feet. I looked into the trees to the right and left of me. I looked behind me. I was hyper-alert and exhausted. I was emotionally drained, concerning myself about land mines and booby traps. During a rest period, I looked up in the sky, and prayed, ‘Oh, Lord, dear God, please take me out of here.’”

When small-arms fire erupted, “the guy who took my place on flank was shot in the left eye, leaving a hole in the back of his head the size of a golf ball. Bullets went through my rucksack; one hit the thigh of the soldier behind me. He cried out in pain. There was yelling, screaming, hollering, explosions, and the sound of automatic weapons fire going on all around me.”

Tyrone was seriously wounded by enemy fire while attempting to help his medic bring wounded comrades to relative safety. “I was hit literally from head to foot,” he recalls. “I nearly bled to death.”

But he didn’t. Medevacked to a hospital in Saigon and then back to the States, he endured a long period of recuperation. Two years after he was inducted, he left the service, with a Bronze Star with ‘V’ device, a Purple Heart, and a 50% service-connected disability rating.

Getting Focused

Like many Vietnam veterans, unresolved feelings about the war that almost took his life lingered on his psyche. For a long time he had a dream: I’m in the jungle, helpless, injured. I’m thinking they’re coming to get me; they’re coming to get me. And I wonder: Will they finish me off? Or will they take me prisoner?

As he became convinced of the futility of the war effort – if people only knew what was really going on, they would stop the war, he believed – so, too, emerged a consciousness to help his fellow veterans.

But first he needed an education.

A product of Philadelphia’s public school system, it was a miracle, Tyrone says, that he even learned to read. Yet the one book he did read, Pearl Buck’s The Good Earth, inspired him. And after he was injured and hospitalized, reading became his salvation. “Otherwise I would have lost my mind,” he says.

Armed with a determination to improve himself, and aided by the GI Bill, he went to college, first to Pierce Junior College in Center City, Philadelphia, then on to LaSalle University, where he earned his bachelor’s degree, having majored in sociology and minored in psychology. “And the world opened up for me,” he smiles.

While attending school, he worked as a clerk for the VA. Less than enthralled with how many VA employees treated those whom they had an obligation to serve, he quit. In 1977 he began his career with the state Department of Labor as a disabled veteran’s outreach program specialist. And he found himself.

“To hear a fellow veteran tell me, ‘I come to you and I get all this assistance in 30 minutes after being given the run-around everywhere else I’ve been,’ tells me I’m doing the right thing,” he reflects.

And he is.

Winning Recognition

Tyrone’s efforts on behalf of his fellow veterans have been applauded. In 1990, he was presented with the Dean K. Phillips Award by the National Veterans Training Institute at the University of Denver for his professional leadership and contributions in caring enough to “make a difference.” Two years later he was accorded the highest honor the International Association of Personnel in Employment Security bestows, the Award of Merit.

Two years after that he was acknowledged by State Senator Allyson Schwartz for his leadership on issues of concern to veterans, who cited his work as host of the Veterans’ Hour radio show aired the first Saturday of each month on a local radio station, WDAS-AM.

In 1999, Tyrone was presented with twin accolades from his Department of Labor: the Pride Award, for his initiative and willingness to serve his clients and the veterans community at large on and off the job, and for the innovative methods he’d initiated to enable veterans to improve their self-esteem and become productive members of their community; and the Keystone Award, for his commitment to elevate the profile of the veterans job center by providing quality services. Hitting the trifecta in ’99, Tyrone was given the Legion of Honor Award by the Chapel of Four Chaplains, in recognition of his selfless service without regard to race, religion, or creed.

In addition to his daily efforts on behalf of veterans, Tyrone’s creative impulses found an outlet in writing – in addition to his book, War Aftermath Depose, his poetry has achieved critical praise – and in producing – “Letters from the Attic,” a play about the contributions of black American war veterans.

When Tyrone T. Dancy went into the Army, he was young and strong and scarless. When he left two years later, his body was a mess of scars, and his hearing was permanently damaged. He was angry. But he refused to succumb. During the long and agonizing months of his hospitalization, “there was this one guy who was in worse shape than I was: he’d lost an eye and a leg. So I buried a lot of my anger and recalculated my own attitude.”

Tyrone Dancy channeled whatever lingering bitterness that was sullying his soul into a constructive and productive career – one that has aided thousands of veterans in his home town and beyond.

Special thanks to Deborah Ross, “Veterans Hour” librarian, who wrote to VeteransAdvantage about her hero, Tyrone Dancy.