Military & Veterans Life

Cover Story: Our Trip to Normandy

Rea Elias

My husband, Albert, who served with the 1st Engineer Special Brigade, landed on Utah beach at D plus four hours. Although he never spoke to his family about his experience there, when he would get together with one of his Army buddies, they would reminisce about their times in Africa, England, France, and finally Okinawa, and remember funny stories but not the gun fire.

Five years ago, Albert underwent open-heart surgery. Since then, he has been more open with us about his time in the war. He talks about how “awesome” the whole event was. How close he came to being killed….how unbelievable it was to see his buddies falling all around him….the sight of all the many boats coming to shore, not knowing really where he was and looking to find his friends. Hard to believe that “I really was there and lived through the whole thing.”

We have very good friends, Janie and Michael, who are the same age as our sons. Not long ago, they asked if we might want to travel with them to Normandy. We were thrilled at their offer, and accepted immediately. They planned the entire trip, and May 3, 2001, we boarded British Air and began our voyage of discovery for our friends and me, and of rediscovery for my husband.

After spending three days in London visiting old friends, we took the train through the Chunnel to Paris. There we were met by Chris Bart, an expatriate American who has lived there for 20 years and who would be our driver. Then we drove to Normandy, first to Port en Bessin and then on to La Cheneviere, where we were met by Jim Dickey, a retired general, who would serve as our guide.

Our first stop was the American Cemetery, where we were given a special tour of the grounds. I came across a group of markers of men who had died at the same hour on the same day; I remember thinking they must have served on a bomber that had been shot down. Later, when Albert signed the guest book, while overlooking the reflecting pond, taps were played. When the cemetery director, Gene Dellinger, presented Albert with American and French flags used in services on Memorial Day, none of us had a dry eye.

It Still Fits

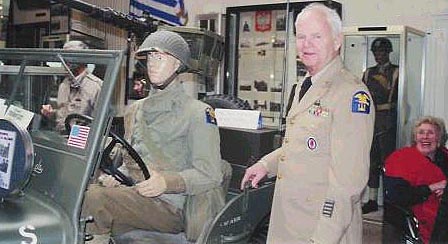

The next day, Albert put on his uniform, the same one he had worn 57 years ago.

On tap that day was a visit to the Museum at Arromanches, where Jim had arranged for a viewing of a re-creation, in miniature, of D-Day on Omaha Beach. Viewing this display, we came to realize the magnitude and complexity of that invasion. We could only imagine what Albert and the men he went ashore with had gone through. What they must have felt while heading to the beach, and storming ashore. How they must have reacted to the bodies along the beach, and to the fire from the Germans.

At the end of our visit, the museum director took Albert into his office to sign a special register, and then presented him with a medal and a commemorative paperweight. This gesture touched Albert very deeply.

We went from Arromanches to a little lunch place on the waterfront. There we met a American couple and their young child. He was in the foreign service, assigned to the embassy in St. Petersburg, Russia. He was in Normandy to see where the tide had turned against Hitler. And he was thrilled to meet Albert. He promised to one day tell his son, when he was old enough to understand, that on this trip to Normandy, they had met one of those who had helped to win the war.

After lunch, we went to Utah Beach. Wherever we went, people would greet us. They would shake hands with Albert and thank him. While the rest of our little party took a walk on the beach, I was sitting in my chair – a bout with polio 52 years ago affects my mobility, but not my spirit – when a woman came up to me. Without saying a word, she handed me a shell. This simple gesture moved me beyond words.

Later on, we met a young man from Colorado who told us he is establishing a museum about D-Day. He, too, was thrilled to meet someone who had fought. He interviewed Albert, and videotaped him on the beach. Albert felt appreciated.

At a memorial to Albert's outfit over a German bunker, we were disappointed at first when the insignias were missing. We learned why two weeks later, when Tom Hanks, who starred in the epic about D-Day, Saving Private Ryan, made a presentation for the 57th anniversary of D-Day in front of this bunker. He was there to film the series on HBO “Band of Brothers”

At Utah Beach there is a museum with an old Higgins boat that had been used in the invasion. This was of particular interest to Albert who, before he was sent overseas, he had been supervising the shipping of the Higgins boats in New Orleans. They were sent over in boxes and assembled in England. Albert’s job was to ensure that all the necessary pieces were packed in each box.

Before we left the museum, Albert was presented with another certificate acknowledging his participation in D-Day.

We went from there to the German cemetery, Wesel 111. How different it is than ours: it is a large field with five black crosses scattered seemingly at random. Hundreds of brass plates, each with two names, are placed on the grass.

As we were looking around, a German woman dressed in black was checking the wreaths at the large memorial. While I am sure she was just another widow, her presence brought chills to us. She had the demeanor of the old Gestapo and it brought to mind frightening pictures.

The next day we toured the Overlord route, taken by many of the Allied troops as they pushed into France. Markers along this route dubbed it the “road to freedom.” We stayed on this road to Pointe du Hoc, where U.S. Army Rangers scaled the 30-meter cliffs to knock out German artillery. We could still see some of the craters caused by American bombs, as well as some German bunkers. We also viewed the large cement monument made to look like a Ranger dagger thrust between the rocks.

We went on to Ste. Mere Eglise a village where paratroopers landed. A scene in the movie, The Longest Day, based on the book by Cornelius Ryan, shows one of the paratroopers caught on the church steeple, his parachute snagged. He hung there, helpless, until the Germans shot him down.

We were in a little restaurant there when the waiter overheard our conversation and informed the rest of the diners that a veteran was there. A lovely Frenchwoman came to our table and said to Albert, “I just want to shake your hand. My daughter was born on June 6th and would not be here if not for soldiers like you.” Another evening, after dinner at La Cheneviere , a Dutch couple came up to us while we were having a night cap and again shook Albert's hand and thanked him. They just wanted to tell him, they said, how much it meant to them to have met someone who was there. Another scene a few days later: In a jewelry store in Honfleur, the owner and her daughter began crying when they found out that Albert had been one of the soldiers during D-Day. “Look at me,” she said to us. “I would not be here if not for you.”

Our last memorial stop was in Caen, a town that had been leveled during the fighting. The museum there is astonishing. A visitor walks up a ramp flanked with photographs and small monitors that tell the story of Caen after World War I and during WWII. In a large screening room (the screen is split to show the Allies on one side, the Germans on the other), you relive the invasion. This was, I felt, the most moving part of the trip for Albert. As we were watching the filmed sequences, which made you feel you really were in the middle of the battle, Albert just held on to me.

Reflecting on this trip, we realized how difficult it must have been for the soldiers of both sides, not to mention the civilians in the towns and villages who were caught up in the fighting. We also came to appreciate even more what our country was able to accomplish in World War II– and the sacrifice of the young men, and women, who were sent off to fight. Albert was gone for two and half years, and when he returned home, we got married and had a week together before he was gone to Okinawa for another year. We look back and wonder how we were able to do it.