HeroVet: Marine Vet Chuck Meadows Makes Peace Clearing Unexploded Relics of War

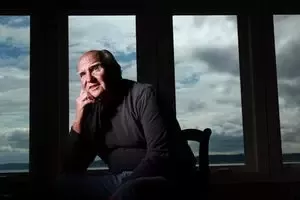

He is unremarkable in appearance. He could be a college professor or an accountant, a small-businessman, maybe. To borrow a cliché, though: Never, ever judge a book by its cover. Chuck Meadows is a career Marine, seared by combat, who now makes peace with those against whom he waged war.

Chuck Meadows is the executive director of PeaceTrees Vietnam, the first organization granted approval to remove landmines and unexploded ordnance in Vietnam. His professional focus is to locate, and clear, the tons of bombs and rockets and mortars still littering Quang Tri, Vietnam, the northernmost province in what had been I Corps, where some of the fiercest fighting of the “American War” took place, where people still fall victim to high explosives that failed to detonate during the long years of conflict.

“Since 1964,” Chuck Meadows told an audience recently at the New Jersey Vietnam Veterans Memorial, where he was a panelist during a program focusing on the Vietnamese experience in America, “I have thought about Vietnam every day of my life.” His mission now is one of peace: to help reverse the legacy of war. With PeaceTrees, a handful of Americans work with the Vietnamese not only to clear the land but to teach the people about the dangers that lurk just below its surface.

In Quang Tri province alone, Chuck explained, more ordnance was expended than all the bombs dropped on all of Europe during all of World War II. While the fighting may have ended in 1975, Vietnamese are being killed and maimed just about every week by this detritus of war. In some cases, a farmer is working in his rice paddy when his water buffalo steps on a bomb long buried in the muck and mire. Or some kids find this odd-looking piece of metal and start to play with it, oblivious to its often deadly consequences. Or some clueless “entrepreneur” seeking scrap metal begins cutting up what he believes to be a harmless relic of war and gets blown to smithereens.

As a Marine, Chuck Meadows’ first commandment was: Always take care of your troops. Now, it’s: Take care of the people. Which is, he said, simply “a redirecting of compassion.”

Early Bird

Chuck Meadows, who hails from Beaverton, Oregon, was commissioned in 1961, having completed Marine ROTC at Oregon State University. His first tour in Vietnam was brief: as a rifle company commander, Lieutenant Meadows arrived in Chu Lai in May 1965 in the second wave of Marines, part of the initial buildup of American troops. His job then was simple: take the beachhead and provide security for the construction of an airfield at Chu Lai. In July, he was sent back to the States.

Eighteen months later, Captain Meadows took a company through training before deployment to Okinawa. In November 1967, he was sent back to Vietnam. He was assigned to Golf Company, 2nd Battalion, 5th Marines, part of the 1st Marine Division, based initially at An Hoa west of Danang and then at Phu Bai. On 30 January 1968, he was in charge of a special reaction company at Phu Bai when Communist units attacked cities and military bases across South Vietnam in what would come to be known as the Tet Offensive.

“We were sent a couple of klicks in front of our lines to monitor enemy movement,” he said. “We could hear the mortars being fired into the camp.” Oddly enough, it was safer outside the perimeter than in the camp, he said.

The next day, his company received orders: Go to Hue city to escort the commanding general of the 1st ARVN Division to safety. One company that had been sent out earlier had run into trouble, so Golf Company “grounded our packs and trucked into Hue.” Just over the bridge in the city, they got shot out of their trucks.

The Marines fought their way to the MACV compound, policing up the dead and wounded of Alpha 1/1 along the way. The situation, they found, was as murky as paddy water; it was “unclear” just exactly what was going on. Chuck Meadows was told to get his men over to the Citadel, the center of the ancient imperial city of Hue.

As the first elements of Golf Company reached the crest of the bridge over the Perfume River, they came under intense small-arms, rocket, machinegun, and mortar fire. It was there that he witnessed one of the signal acts of courage under fire.

“A squad leader, Corporal Lester Tully, and his people maneuvered down the side of the bridge, which was no easy feat, to take out the machine-gun bunker with hand grenades,” he said. For his act of bravery at considerable risk to himself, Lester Tully was awarded the Silver Star.

As Golf Company pushed on, it didn’t take Chuck Meadows to realize that “we didn’t have the strength, the size, or the support to go much further.” Late that afternoon they managed to make it back to the MACV compound. Out of 160 men who started the day, 45 had become casualties. Their losses weren’t as bad as those suffered by Alpha Company, though, which had lost all its officers and half its troops.

For Chuck Meadows, the 31st of January was by far the most difficult day he had experienced in combat. “We had to confront the unknown, with very limited intelligence as to what was going on,” he reflected. “We really earned our pay.”

While the Tet Offensive was a costly defeat for the Communists, one that succeeded in eliminating much of the infrastructure of the local Viet Cong, it was a watershed in determining American policy in Vietnam. After years of having been told that the “light at the end of the tunnel” was growing ever brighter, many Americans could not understand how an almost-defeated enemy could mount such an attack.

None of this, though, was Chuck Meadows’ concern. He had a job to do and he and his men did it. Over the next week and a half, along with two other rifle companies from the 2nd Battalion, 5th Marines, Golf Company fought to clear the south side of Hue city of its invaders. The last elements of the NVA weren’t eliminated until some 40 days after they first entered the Citadel.

In March, the Marines were relieved by units of the Army. In April, Chuck Meadows, who was then 28 years old, headed back to The World. He was proud to have had the opportunity to lead young Marines in doing work we were well-trained to do. He was very “secure and comfortable” in the leadership he was able to provide, and in the ethos of the Corps that made taking care of one another one of the highest priorities for a Marine.

Retracing Footsteps

Looking back from the perspective of a third of a century, Chuck is struck by the “seeming inability of America’s leaders and decision-makers, both political and military, to define our true national objectives and to make decisions based on those objectives. Because they weren’t clear from the start, they were subject to reinterpretation and change.

“We never got to finish,” he believes, “the job we were sent to do.”

PeaceTrees, though, has given him an objective: to heal the land and to build friendships while eliminating a continuing source of death and devastation. And to try to give young people the chance to live in their tomorrows and not in our yesterdays. For Chuck, this new mission helps “bring closure with a sense of doing something honorable.” It has also enabled him to connect with other veterans who have similar sentiments.

The Vietnamese, who are genuinely grateful for efforts like PeaceTrees to heal and to rebuild, “have taught me a lot,” Chuck said. “They have moved on. What happened, happened. While they cannot escape the fact of the war, they don’t dwell on it.”

On one of his first trips back to Vietnam as executive director of PeaceTrees, Chuck Meadows returned to Hue, and spent an afternoon retracing the path he and his Marines had taken some 30 years before. What had taken days in the chaos of battle now took less than an afternoon. As he walked in a now vibrant city, he wondered about what might have been, and reflected on the immense proportions of the task at hand: he cites figures estimating that less than 20 percent of the hundreds of thousands of tons of unexploded ordnance have been cleared. So much to do, with never enough “assets” to accomplish all he would like.

But, he said, “we do what we can to help when we can, and that’s the best any individual can do.”

Image credit: https://www.seattletimes.com/seattle-news/library-in-vietnam-honors-bainbridge-island-veteran/