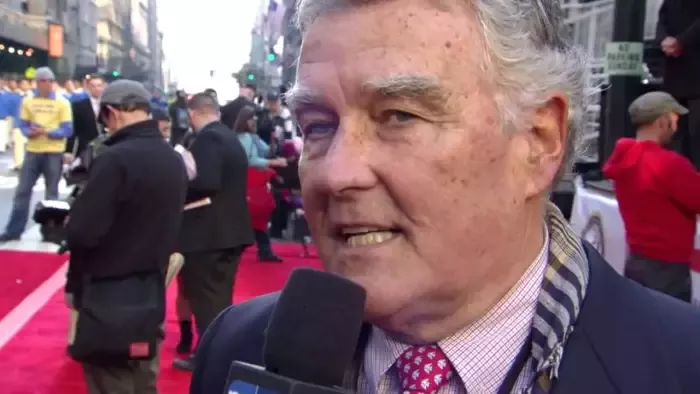

HeroVet: Vince McGowan, Reviving NYC's Veteran Community

The general sat, stone-faced, as the sergeant pointed to the briefing map and gave his standard 15-minute spiel about the successes of the Combined Action Program in the village of Binh Nghia.

General Creighton Abrams had choppered in that morning to Fort Page, the outpost manned by a squad of Marines and Vietnamese militia in the village of 5,000 farmers, a few kilometers from the now infamous hamlet of My Lai. He sat, impassive, chomping on a cigar, not even cracking a smile at one of Sgt. Vincent McGowan’s jokes.

After eight minutes, Abrams was gone. And McGowan, leader of the 12-man squad, thought he had blown it, that the man who would one day succeed General William Westmoreland as commander of U. S. forces in Vietnam didn’t comprehend that in one small area of operations, a committed and confident band of Marines was winning the war, using small-unit tactics and establishing credibility with the villagers to best the Viet Cong at their own game.

Back in 1966, when Vince McGowan met General Abrams for the first and only time, when the American military presence in Vietnam was still young, many thought that the war was still winnable. The Marines at Fort Page, named after the first of their number to be killed in action, patrolled every night. They worked in concert with Vietnamese Popular Forces. They won most of the firefights in which they engaged. But mostly, they won hearts and minds.

"We were a showcase unit," McGowan says today from his office in Battery Park City, a stone’s throw from the smoulding ruin of the Twin Towers, where he is assistant director and director of operations for the Battery Park City Parks Conservancy responsible for maintaining 96 acres, two marinas, 17 buildings, two schools, and a ferry terminal.

"We helped this village reach a degree of democratic rule. We helped write the book on how CAP units should operate. And the techniques we used were eventually incorporated into Marine Corps tactics."

Despite all its might, the American military did not have many such successes in Vietnam.

Parallel Construction

Vince McGowan grew up in a five-story tenement on the West Side of Manhattan, at a time when Hell’s Kitchen was one of New York’s rough-and-tumble neighborhoods, a stomping ground for a slew of rival gangs. A onetime Golden Gloves boxer who had some success in the ring, McGowan joined the Marines in 1964, just before his eighteenth birthday.

In the Corps, the brash high-school dropout found himself. He achieved top honors in just about anything he took on, including the Dress Blue award out of Paris Island, where he went to boot camp. Ignoring the maxim, he volunteered - for sea school, jump school, amphibious warfare school. After a year in the Mediterranean theatre of operations participating in mock warfare exercises, Corporal McGowan went to Vietnam.

On his third day in country, his reaction squad was called to relieve the beleaguered Special Forces camp at Ba To, which was about to be overrun. He was in the second chopper heading into a very hot LZ. The lead bird was blown out of the sky. For McGowan, this was "a real shocker," a true baptism of fire. They did manage to secure the perimeter, averting defeat.

After working with the Montagnards, the indigenous mountain tribes of the Central Highlands, many of whom became loyal allies of the Americans, he took on the role of squad leader at Fort Page, which had been overrun by a battalion of North Vietnamese Army regulars. For McGowan, who was fascinated by the strange and exotic culture he found in Vietnam, this was an opportunity "to engage people in a mission that really was important." Growing up where he did, in a place where "a few guys on the block can control everything," he saw parallels in villages like Binh Nghia, where a "few guys" - the Viet Cong - could dominate a "silent majority" without a groundswell of popular support.

He also saw parallels in Ireland, the home of his forebears. There, the Black and Tans conscripted men from the families along the coast of Galway near Donegal, from which his parents had emigrated.

Vince McGowan used his Marine training and the knowledge he had gleaned from the streets of his city to win some battles in the long unquiet war.

Under McGowan, working with and getting to know the villagers and gaining their trust was as important to achieving success as was perfecting small-unit tactics - patrolling every night, seeking to engage the enemy and fighting them on their own terms. During his time in Binh Nghia, McGowan and his men engaged in plenty of firefights.

"One day, some of the village leaders gathered in a small town we called ‘Nuoc Mam,’" he recalls. "The VC attacked. The Army unit with responsibility for that town did not know what to do. An Army colonel ordered us to do nothing. But these were our people there. So two of us - the rest of the guys were out on patrol - packed up our gear and ran the three miles to the town. I must have been carrying 25 grenades, 1,500 rounds of ammunition, three LAWs.

"We attacked the VC, who weren’t expecting any real resistance. We were relentless. They used civilians as shields, but we had to press on. No quarter was given or taken. We routed them."

With Binh Nghia pacified, the decision was made on high to let the militia take over. McGowan and his men went on to establish another CAP unit on the My Lai peninsula. But for McGowan, 15 months in Vietnam was enough. "I had started to like it there too much," he reflects. He went back to The World.

Years of Disillusion

McGowan spent a year working with the RAND Corporation, using his village smarts to devise a civics program to be incorporated into the pacification effort in Vietnam. In short order, though, he became disenchanted by events in the States that mocked the men fighting under the banner of Old Glory. "The American people didn’t support us," he says simply. And with any possibility of victory slipping away, those who had fought the war bore the brunt of the blame.

When he returned home in 1968, which was to be the bloodiest year of the war, "you were a bum." Disgusted, McGowan left the country, spending years down in Guatemala and southern Mexico. "I had little tolerance for the disrespect we were accorded," he says. "I would have wound up in jail if I didn’t leave."

New York was his home, however, and he returned in 1973. For ten years he owned bars and nightclubs. Lessons he’d cultivated in Vietnam - learn to trust your instincts and you’ll know what to do and when to do it - served him well. Yet there was a hole in his heart. "Our service was never validated," he says. "We had guys who never wavered, who sacrificed their all, and who never were appreciated for what they did. And that’s still a problem to me."

McGowan cites an excerpt of a poem by Tom Oathout inscribed on the New York Vietnam Veterans Memorial in lower Manhattan: Mother I am cursed - I’m a soldier when soldiers aren’t in fashion. He was determined to alter the perception by veterans of themselves, and of veterans by the rest of America.

Vince McGowan became an activist. He embraced the nascent veterans movement because, he says, "We couldn’t ignore what had happened. We had to come to terms with this or it would eat its way through us in the most unanticipated ways."

He became one of the original members of Manhattan Chapter 126 of Vietnam Veterans of America, whose board he chaired. He worked his way up to first vice commander of the American Legion post in New York City, and ran their parades for three years.

Situated in a multilevel outdoor plaza, with a view of the East River, New York's Vietnam Veterans memorial is a unique and moving tribute to the men and women who sacrificed their lives in the war. On a large wall of green glass blocks, excerpts from personal letters and news stories are etched into the glass in varying fonts.

This role, however, was an exercise in frustration. And when the Legion decided to forego its longtime sponsorship of the Veterans Day Parade, McGowan dusted off the 1912 charter of the United War Veterans Council, originally formed to honor the last of the city’s Civil War veterans. He got a revivified Council recognized by the State of New York, and went to work.

The Council has revived the once-moribund parades on Veterans Day and on Memorial Day. This year’s Veterans Day parade featured 10,000 marchers in 70 individual units, with six bands and five floats. "We’ve reestablished these parades as part of the New York scene," he says, not without satisfaction.

His powers of persuasion were instrumental in raising the money - including almost $2 million in funding from the city - to reconstruct Vietnam Veterans Plaza, which had grown decrepit in the years since the dedication of New York City’s Vietnam Veterans Memorial in 1985.

And on November 9th, Vince McGowan seamlessly MC’ed the ceremony rededicating the plaza, a ceremony in which one general, two Medal of Honor recipients, and the head of the VA were among a crowd of 2,000 who were buoyed by the events of the day - and the very real improvements to a place of contemplation and reflection.

Some of them even knew enough to appreciate the yeoman efforts of Vince McGowan, the street-smart sergeant who couldn’t elicit a grunt of approval from General Abrams three decades before.

The story of the CAP team failures and successes, joys and failures, can be found in The Village, by F. J. West, Jr., published by the University of Wisconsin Press in 1985. Although out of print, this book, which deserves an audience, can be found through some used book services.

Image credit: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZYoXs9ZnbyU